| By Roger Strong, Jr. |

As expected, Barbie was the most popular costume this Halloween. Less than two weeks later, Veterans Day will pay homage to the people who fought in America’s wars, including scientists like J. Robert Oppenheimer. And so, even though the summer movie season is over, the “Barbenheimer” phenomenon is still very much alive. But there’s more to this story than just record-breaking box office returns and fun costumes.

While they’re very different in terms of style and substance, the two films are linked not just by their release dates but by some intriguing commonalities. Both movies explore the complicated legacies of figures who loom large in American history. Both focus on subjects who’ve contributed a great deal—for better and worse—to our national landscape.

For those who have seen the movies and are looking to learn more about these cultural icons, here are some fun and fascinating facts behind the subjects of these blockbuster films.

The Real Oppenheimer

As Oppenheimer makes clear, theoretical physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer was a polarizing figure who came under intense government scrutiny for his beliefs, associations, and public statements—which ultimately led to his loss of security privileges at the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC).

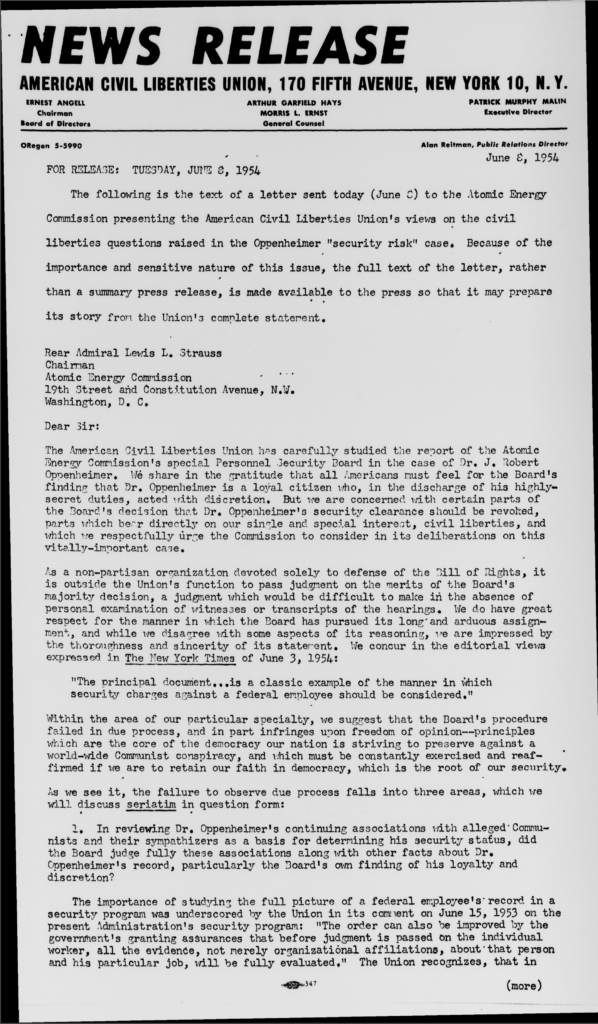

Having first worked with the FBI File of J. Robert Oppenheimer on microfilm in the mid-’90s, I thought it would be interesting to cross-search this now-digitized resource in Gale’s Political Extremism archive alongside other primary sources in Gale’s databases. As I dove into newspapers, manuscripts, and government documents, I was intrigued to learn that the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) wrote a three-page letter to AEC chairman Lewis Strauss protesting the Personnel Security Board’s decision to revoke Oppenheimer’s security clearance. The ACLU’s letter provides an interesting jumping-off point for thinking about the application of civil liberties in the context of government service and national security.

Cases-Civilian: Oppenheimer, J. Robert. 1954-1955. MS Box 883, Folder 19, Item 1226, Years of Expansion, 1950-1990: Series 3: Subject Files: Freedom of Belief, Expression, and Association, 1939-1988. Mudd Library, Princeton University. The Making of Modern Law: American Civil Liberties Union Papers (accessed November 8, 2023). https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/VSGBQT433488977/GDCS?u=rstrong&sid=bookmark-GDCS&xid=b36b598b&pg=2.

Citing the board’s statement arguing that Oppenheimer did not show “enthusiastic support” for the government’s H-bomb program, the ACLU wrote: “In our view, the idea of ‘enthusiastic support’ of a government policy as a security criteria runs contrary to the whole democratic concept of a free society based on free thought. The whole idea of a democratic society envisions the working together of men with enthusiasm for and against a policy, and even men without definite enthusiasm. For it is this clash of views, this exercise of diversity, that has produced both the spiritual and material advances of American democracy.”

A year later in 1955, the ACLU again supported Oppenheimer when the president of the University of Washington prohibited the physics department from hiring him as a guest lecturer for a series of seminars on campus:

Cases: Oppenheimer, J. Robert: Lecture Ban. 1955. TS Years of Expansion, 1950–1990: Series 3: Subject Files: Freedom of Belief, Expression, and Association, 1939–1988 Box 728, Folder 37, Item 993. Mudd Library, Princeton University. The Making of Modern Law: American Civil Liberties Union Papers, link.gale.com/apps/doc/REZMRW169989028/GDCS?u=rstrong&sid=bookmark-GDCS&xid=0d2e29a8&pg=9. Accessed 15 Aug. 2023.

With similar debates occurring over campus free speech today, this incident reminds us that we can find numerous echoes of history amidst current events.

Then as now, many Americans distrusted Russia. In a declassified letter from September 1954, a legal attaché from the American Embassy in London warned Brigadier William Magan in the British Secret Service that it was rumored Oppenheimer might try to defect to Russia that month by way of England and then France. “I would appreciate being advised when Oppenheimer next visits the United Kingdom,” the letter states. “I would also appreciate your considering the advisability of placing him under observation while here.” As far as we know, no such attempt was actually made.

Though Oppenheimer’s biggest legacy was the development of the atomic bomb, he also played a role, however indirectly, in the history of airport security. As recently as a few years ago, an article in the Smithsonian Institution’s Air & Space Magazine described the effect of Oppenheimer’s comments during a Senate atomic energy hearing in 1945 about the ease of smuggling potential weapons-grade uranium, and how it led our national security to install radiation detectors at airports.

The “Real” Barbie

As Oppenheimer’s career was winding down in the late 1950s and early ’60s, Barbie’s was just getting started. She was introduced in 1959 at the American International Toy Fair, and by 1967, more than 1.3 million children had become part of the official Barbie Fan Club. That was about 10 percent of the population of young girls in the United States at the time, as reported by the Berkeley Barb, a weekly underground civil rights newspaper, in an article titled “Assault on Childhood” (and found in Gale’s Women and Gender Studies archive).

In reviewing Ron Goulart’s 1970 book The Assault on Childhood, the Berkeley Barb article repeated Goulart’s argument that Barbie was contributing to the rampant consumerism of the modern American child. “To buy all the clothes and props Mattel offers to go along with Barbie would cost several hundred dollars,” the article notes. “Barbie actually lives better than a good 60 percent of the real children in this country.”

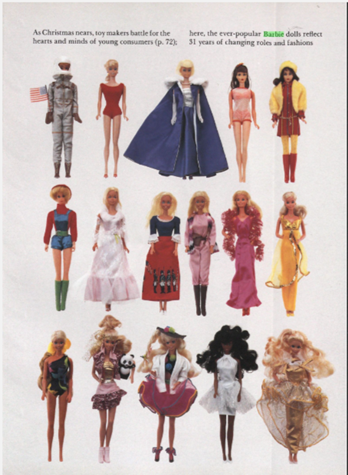

Flash forward to a 1989 article in Smithsonian Magazine, which noted that Mattel became the fourth-largest maker of women’s garments in the United States through its production of more than 100 new Barbie outfits each year. Over 31 years, this amounted to 75 million yards of fabric! The article states that a whopping 90 percent of girls ages 3–11 owned one or more of the dolls, and if all the Barbies sold in that 31-year period were laid end to end, they would circle the globe three-and-a-half times.

By 2001, two Barbies were sold every second, expanding Mattel’s franchise to more than $1 billion in value. Barbie even began signing Nutcracker sponsorship contracts with the English National Ballet. The Times of London reported in 2006 that Barbie over the years had adopted more than 40 pets, including 21 dogs, 14 horses, three ponies, six cats, a parrot, a chimpanzee, a panda, a lion cub, a giraffe, and even a zebra.

Barbie’s outfits over the years.

Stewart, Doug. “In the Cutthroat World of Toy Sales, Child’s Play Is Serious Business.” Smithsonian, vol. 20, no. 9, Dec. 1989, pp. 73+. Smithsonian Collections Online, link.gale.com/apps/doc/SWQCHV432678466/GDCS?u=rstrong&sid=bookmark-GDCS&xid=ebf64288. Accessed 17 Aug. 2023.

The convergence of these two blockbuster movies provides a fun and informative opportunity to think about important issues such as civil rights, consumerism, and the outsized roles the films’ subjects have played in our society. My deep dive into historical archives provided a wealth of rich material about Barbie and Oppenheimer that broadened the insights revealed in these films.

Roger Strong, Jr., is the vice president of global academic sales for Gale.