| By J. Robert Parks |

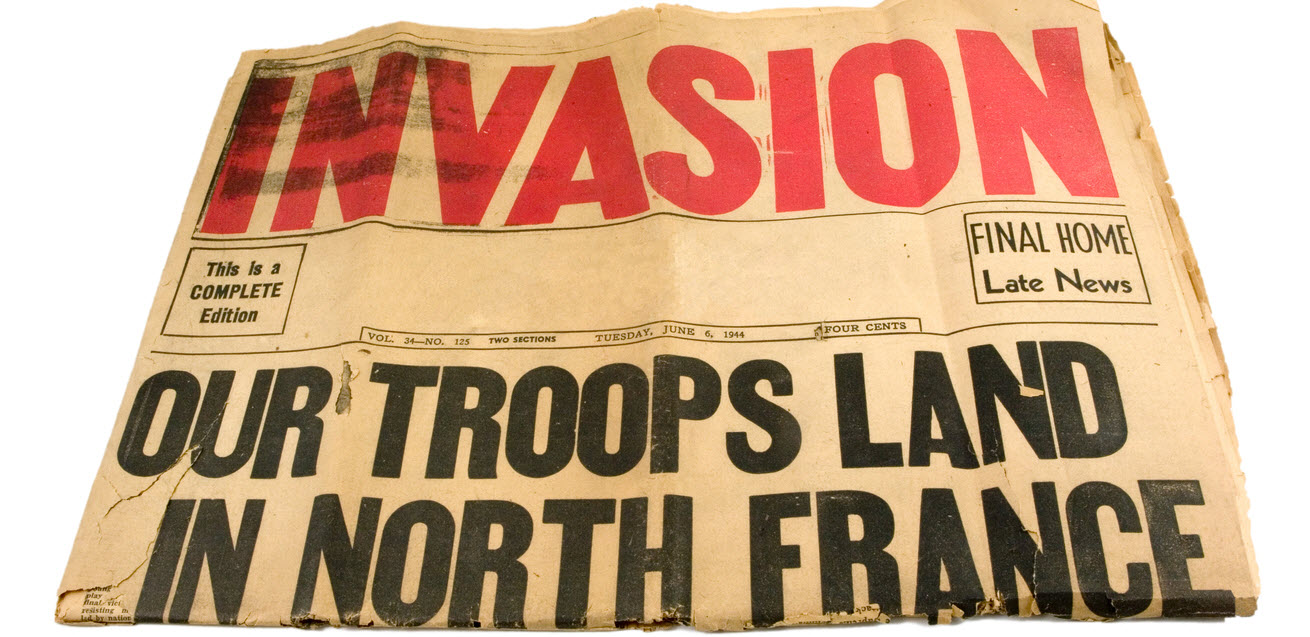

Although many people date the rise of Fascism to 1933, when the National Socialist (Nazi) Party took control of Germany, the Fascist Party came to power in Italy more than a decade earlier, when Benito Mussolini and thousands of his followers marched on Rome. The march took place on October 28 and 29, 1922, and it precipitated the collapse of the Italian government. On October 31, King Victor Emmanuel III named Mussolini the new prime minister, ushering in more than two decades of Fascist rule in Italy. Gale In Context: World History provides a number of resources for librarians and teachers to help students understand what Fascism is and how it came to prevail in Italy.

Mussolini started the National Fascist Party in 1919, calling his followers fasci di combattimento, or combat bands, and he urged Italy’s various groups to work together. Mussolini had been a member of the Socialist Party before World War I, but the events of the war pushed him to embrace a militaristic form of nationalism. Mussolini tapped into the resentments many Italians had about World War I and the fears that many middle-class Italians had about the spread of socialism. His bombastic rallies gained more notoriety, and his followers soon began wearing black shirts.

Beginning in 1920, Fascist militias, known as squadrismo, started attacking trade unionists and other left-wing organizers. Their violence intensified in May 1922, as the Fascists looked to destroy socialist organizations in the country and prevent any kind of alliance between labor unions and Catholic organizations. The increasing violence pushed the Italian Alliance for Labor to call for a general strike on August 1, 1922, known as the Legalitarian Strike. The strike’s organizers hoped to counter the intimidation the Fascists thrived on and to restore legality in Italian politics (hence the strike’s name).

Instead, the strike was a colossal failure. For starters, the duration and aims of it were nebulous, and many anti-Fascist politicians refused to join. Catholic working-class organizations also stayed on the sideline. Instead of creating unity against the Fascists, the strike exposed the deep divisions within the Italian left. Even worse, the idea of a national strike stoked the fears of the middle class about socialism, and they started to look to the Fascists as the only party that could stand up for their concerns. Embracing that idea of being the savior of the country, the Fascist Party declared that it would physically and violently break up the strike if it didn’t end within 48 hours. The strike’s organizers quickly backed down.

Emboldened by that success, Mussolini continued to conduct larger rallies across Italy. On October 24, 1922, he was speaking in front of 40,000 people in Naples when he declared that the Fascists would be given power or they would seize it themselves. He then encouraged the crowd to march on Rome, which had been the tactic of many Italian populists before him. Fascist militias took up the challenge and started driving toward Rome, believing they would soon take control of the government. Indeed, that is what happened.

The government of Prime Minister Luigi Facta wanted to order a state of emergency, but that order required the signature of the king, Victor Emmanuel III. When the king decided to ally with Mussolini, thinking it would strengthen his own power, the democratically elected government collapsed, and the king named Mussolini the new prime minister.

After a year of dictatorial rule, Mussolini consolidated even more power by restricting the activities of the press and labor unions and establishing a new division of the secret police to stamp out dissent. He also inspired a cult of personality around himself, calling himself il Duce (the Leader). Many Italians were thankful for the stability the Fascist dictatorship created, and Mussolini’s popularity soared. Not far away, in Germany, Hitler looked on with admiration. The Beer Hall Putsch, an attempt to overtake the German government, was just a year away.

Other Gale In Context: World History resources educators will find useful include a history of Italy since 1914, an historical analysis of the roots of and ideas behind Fascism, and a point-counterpoint debate on the connections between Fascism and Nazism. The last link also includes Mussolini’s own description of what defines a Fascist

About the Author

J. Robert Parks is a former professor and frequent contributor to Gale InContext: U.S. History and Gale In Context: World History who enjoys thinking about how our understanding of history affects and reflects contemporary culture.