| By Rey Yuan, Gale Ambassador at Rice University |

What comes to your mind when you hear “The Cold War”? The nuclear missile crisis, the “Red Scare,” or perhaps the Iron Curtain speech?

As a history major, I have long been intrigued by the incredible complexities of Cold War historiography. In particular, I have been concerned by how the political maneuvering of the great powers can make us overlook the weight of the war on living individuals. While we often remember East Germany as a symbol of communist failure in the Cold War, we also need to ask ourselves the important question: what did the war mean to ordinary East Germans?

To find the answer, we need to delve into primary sources archives like Gale Primary Sources, which help us access the firsthand records of East German life under the Cold War’s shadow.

“Disparate Twins”: The East-West Competition

Before going into details, it would be helpful to take a look at the overview of East German history in the East Germany from Stalinization to the New Economic Policy, 1950-1963 collection in Gale’s Archives Unbound. On October 7, 1949, the German Democratic Republic (GDR) was established in the Soviet-occupied zone in East Germany in response to the establishment of the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG) in West Germany. Since their very birth, the two German states were entangled in the conflict between the Soviet and Western camps, competing over who represented the “better Germany.”

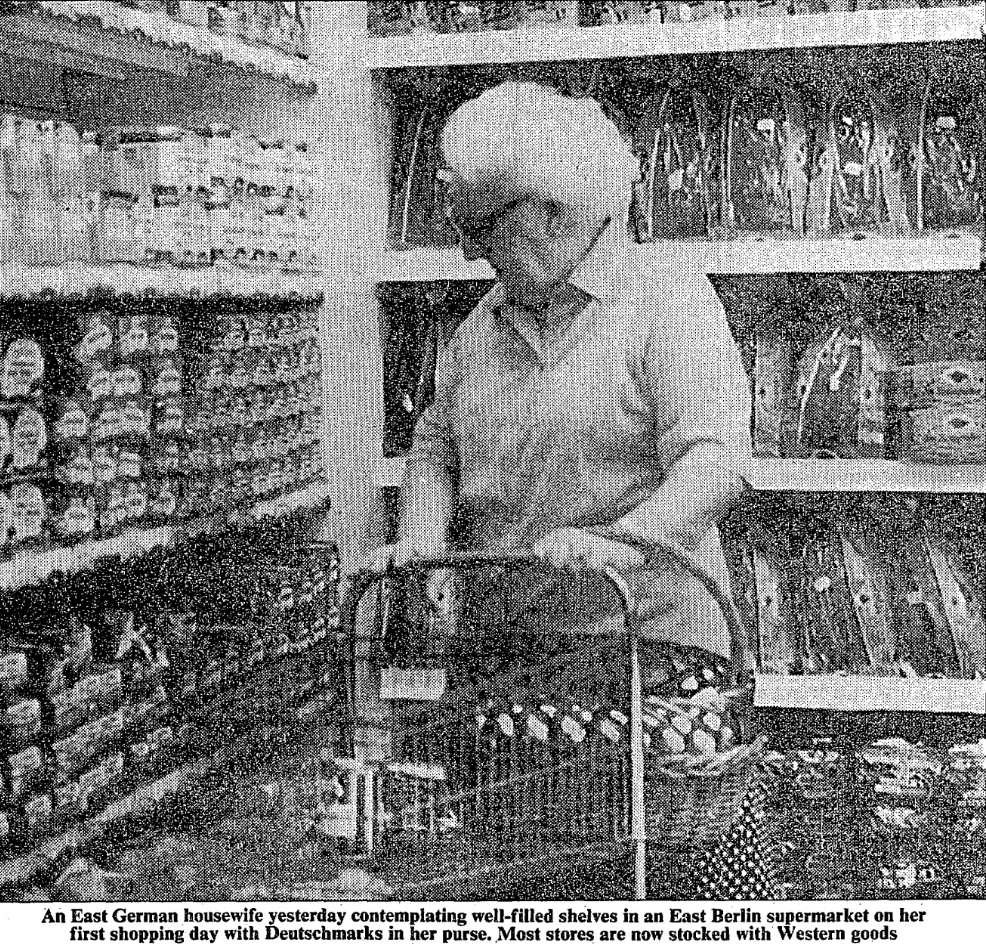

The intensity of the contention could be seen from its mass coverage by newspapers across the world. An article from The Times in 1974, for example, described East and West Germany as “disparate twins in the heart of Europe” in a relationship of “obsessive rivalry.” The article outlined East Germans’ feelings toward the two decades of East-West economic competition; since they witnessed the fragility of the capitalist system during the 1973 oil crisis, they were envying the Western lifestyle less than before. The author argued that because East Germans were not subject to the inflation anxieties of the West, they might be willing to tolerate the higher price of “luxuries” (e.g., cars, televisions) in the East.

Anyhow, East German leadership was bound to ignore the people’s dissatisfaction toward “rather shoddy and expensive consumer goods” and “poor distribution,” as the socialist economy could not be inferior to capitalism. Meanwhile, the shopping experience was only one aspect of East German life afflicted with the ideological fight.

“Agitation and Propaganda”: Politicizing Sports and Cultural Games

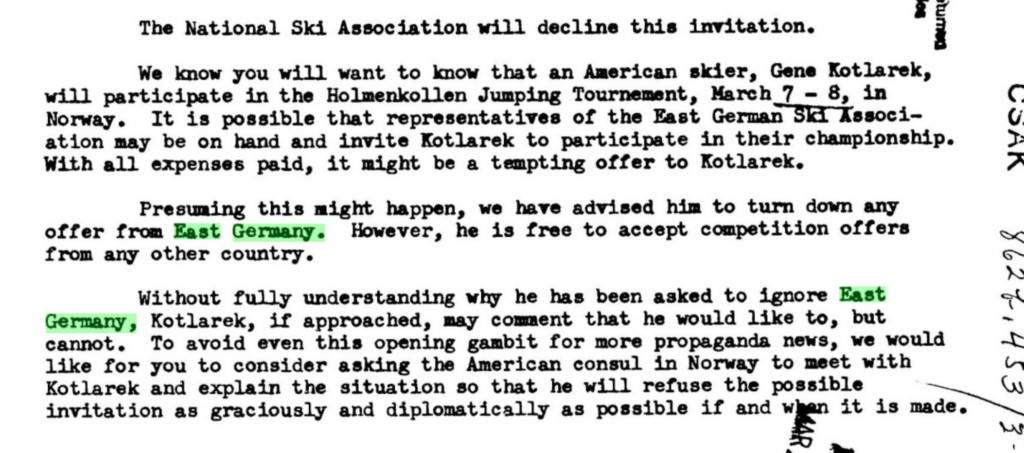

In Gale’s Archives Unbound, the U.S. State Department Decimal Files 762B, 862B, and 962B collection comprehensively documented the U.S. observation and decisions regarding East German internal affairs. The Decimal File 862B.453, classified under the fields of “Sports” and “Recreation,” recorded two incidents that revealed how sports and cultural games in East Germany had been impeded due to Western political suspicion. On March 3, 1959, the National Ski Association of America wrote to the U.S. Office of German Affairs, assuring that it would decline all invitations from the East German Ski Association, as U.S. participation in East German games “might prove embarrassing in the world press.”

Later in November, in a letter to the U.S. Chess Federation, we learn that the West German Embassy reported to the U.S. that invitations to Chess Olympics in the GDR might have been “politically motivated” and served as “vehicles for agitation and propaganda.” Therefore, it would be in the interest of “peace and freedom” that the West refuse to participate. Many reports on similar incidents can be found in Gale Primary Sources, in which the reporters complained that the Western boycott devalued the games and hindered the career of the players.

“Two of Everything”: The Arts and Entertainment at War

In March 1987, an article by the Financial Times vividly portrayed how the GDR and the FRG “compete[d] to be regarded as the German cultural centre.” Both nations increased their cultural budget in order to attract top international performers to their state theaters. The author quipped how in Berlin there were “two of everything: two museums of antiquities, two national galleries and two Islamic, Egyptian and Near Eastern museums” which testified to the ubiquitous competition.

Apart from theaters and museums, the U.S. Department of State report reveals to us that films were also highly politicized; while the East German propagandist saw films as the “most important influential art form” to the “building of Socialism,” the West saw Western films as an effective tool for “blocking the Communization of East Germany.” In addition, there was even a race between the two zoos in Berlin! This document recorded how the U.S. planned to financially support the construction of the West Berlin Zoo, because “serious competition” was expected from the East Berlin Zoo, despite the fact that the East German Zoo director, Karl Schneider, declared that it was not intended to compete with West Berlin because he wished for East-West cooperation in the Association of German Zoo Directors.

Primary records about the rivalry between zoos in East and West Berlin are particularly interesting, as they clearly show how ordinary East Germans like Karl Schneider and Heinrich Dathe, the later director of East Berlin Zoo, were disturbed by the interference of ideological conflicts in their lives. While Schneider expressed that he did not want ill feelings with his co-workers, Dathe was reported to be happy about German unification in 1990, simply because there were no longer political schemes stopping him from doing his beloved job: arranging marriages between rhinos, together with his fellow rhino-keepers in West Berlin.

Conclusion –

From these first-hand reports, we see how political wars are not only about decisions made by politicians in conference rooms, but are inseparably tied to our everyday lives: the commodities we buy, the sports we play, and the theaters we visit. This had been the case for East Germans during the Cold War, and is still true for our world today. Thereby, to understand the shaping of our society’s future, learning about the historical influence of politics in archives like Gale’s Primary Sources is and always will be significant.

Related blogs –

If you enjoyed reading about learning Cold War history through Gale Primary Sources, check out:

- Escaping from Communist East Germany

- Declassified Documents Online: Twentieth Century British Intelligence, Monitoring the World

- “U.S. Disavows Apology, Then Signs It” The Pueblo Incident of 1968

About the Author

About the Author

Rey Yuan is a second year Gale Ambassador at Rice University, majoring in history and classical studies. It is her dream to live for 500 years and master all the fascinating details of human history, but in the short span of her college life, she specializes in Cold War history and historiography. When she is not immersed in the treasury of Gale Primary Sources, she enjoys making digital art, learning foreign languages, and video chatting with her two cats.